MATHS TEACHER TO MILLIONAIRE: The True Story of How Jeffrey Epstein Made His Money... And a Connection With Russia

Let's take an evidence-based dive into Epstein's epic rise, his shady dealings with members of the oppressive Russian Federation, and how he helped the super rich to pay less tax.

Jeffrey Epstein began his adult life in a classroom. Born in Brooklyn in 1953 to a working-class family, the son of a parks department employee, he emerged in the mid-1970s as a mathematics teacher at the elite Dalton School on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. He had attended college but never completed a degree. No finance qualification, no law training, no MBA. What he did possess, colleagues later said, was an unusual fluency with numbers and abstraction. He could see patterns quickly, solve complex problems in his head, move unencumbered through equations that others needed paper to navigate. Dalton was not merely a school. It was a gateway into Manhattan’s political and financial aristocracy. Its classrooms were filled with the children of ambassadors, hedge-fund managers, cabinet members, and Wall Street executives. One of those parents was Alan Greenberg, the powerful chief executive of Bear Stearns. In 1976, Epstein left teaching and joined Bear Stearns as a junior assistant to a trader.

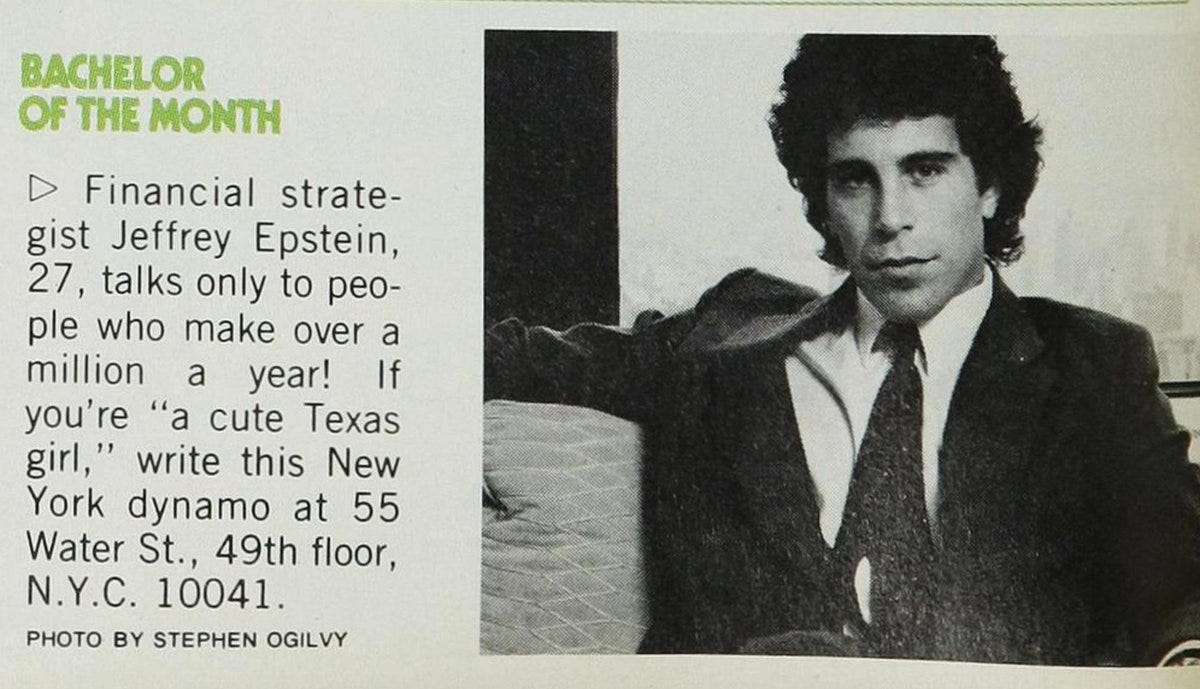

Within four years he had risen to the unlikely status of limited partner, a promotion that stunned those who understood the firm’s rigid hierarchies. Some colleagues later suggested he had a peculiar gift for structuring trades and identifying arbitrage. Others said his real talent lay in cultivating wealthy clients and embedding himself into their confidence. In 1981, at twenty-seven, Epstein left Bear Stearns under circumstances that were never publicly explained. He did not depart with scandal. He did not depart with millions. He left with something far more valuable: contacts.

Within a year he established J. Epstein & Company, presenting it as an exclusive consultancy that served only clients with net worths exceeding one billion dollars. It was a myth designed to manufacture prestige through scarcity. In reality, Epstein at that stage had no such billionaire clientele.

His first serious financial alliance came through Steven Hoffenberg, a volatile New York financier who ran Tower Financial. Tower marketed itself as an accounts-receivable lender. In truth it had metastasised into a vast Ponzi scheme. Hoffenberg later pleaded guilty to what prosecutors described as one of the largest investor frauds in American history, involving losses of more than four hundred and fifty million dollars. He was sentenced to twenty years in federal prison.

Hoffenberg testified under oath that Epstein was deeply involved in Tower’s inner workings, managing cash flows, structuring transactions, and keeping the scheme solvent. Epstein himself was arrested in connection with related financial offences and briefly jailed in Florida. Then, suddenly, the charges against him were dismissed. Hoffenberg went to prison. Epstein walked free. It was the first moment where Epstein stood beside criminal exposure and emerged untouched.

It was also the moment his fortunes pivoted decisively toward Leslie Wexner. By the early 1990s, the businessman and owner of Victoria’s Secret had become the central pillar of Epstein’s financial ascent. In 1991, Wexner granted Epstein a sweeping power of attorney giving him control over checks, loans, property transfers, and asset restructuring across Wexner’s personal and corporate empire. Epstein became, in practice, the financial steward of billions.

In 1998, Wexner transferred the East 71st Street mansion to Epstein through a limited-liability company. The recorded price was nominal. One dollar. The seven-storey townhouse, one of the largest private residences in Manhattan, passed into Epstein’s hands under the legal theory that it settled debts owed for years of financial services. The visual symbolism was unmistakable: a former schoolteacher now in possession of a fortress of generational wealth.

Around the same period Epstein began assembling his physical offshore infrastructure. Through shell companies, he purchased Little St. James in the U.S. Virgin Islands for roughly eight million dollars and later acquired neighbouring Great St. James at far greater cost. Funding sources were never publicly disclosed. The transactions were routed through offshore entities that permanently obscured the origin of the capital.

How did he suddenly get his hands on such huge sums to make these extravagant purchases? Well, clickbait merchants, YouTubers, and the glorified bloggers at the Daily Beast like to insinuate that he was working as some kind of international spy. But the likely truth is far less interesting: He stole it.

Wexner claimed that, whilst Epstein was controlling his financial affairs, Epstein swindled him out of at least $46m.

Wexner’s allegations focus on $46m of investments in a Wexner charitable fund controlled by Epstein. Wexner said that as he severed the relationship, he discovered Epstein had returned only a portion of the money in the fund. He declined to say if he had reported the loss to authorities.

“We discovered that he had misappropriated vast sums of money from me and my family,” Wexner said. “This was, frankly, a tremendous shock, even though it clearly pales in comparison to the unthinkable allegations against him now.”

By 1996, Epstein formally shifted the core registration of his business to the Virgin Islands, establishing Financial Trust Company and later Southern Trust. Under the Virgin Islands Economic Development Commission program, his companies qualified for extraordinary tax privileges: corporate income tax reductions of up to ninety percent, exemptions from gross-receipts taxes, reduced excise duties, and rebates on withholding taxes.

The U.S. Virgin Islands occupies a peculiar position in American law. It is under U.S. sovereignty, but treated as a separate tax jurisdiction. For Epstein, this meant that advisory fees earned from mainland U.S. clients could be booked through Virgin Islands entities and legally taxed at a fraction of what would have been owed in New York. It was offshore without appearing foreign. This was the same logic exploited by global tycoons whose empires run through island jurisdictions, including figures such as Richard Branson, whose companies for decades have routed ownership, licensing, and profits through low-tax island regimes. Epstein mastered both worlds at once: the private offshore universe of international billionaires and the quasi-domestic offshore territory used by American elites.

Internal banking records later showed Epstein routing massive wire transfers through Virgin Islands entities labeled only as “consulting” or “services,” with layered shell companies shielding beneficial ownership. Prosecutors would later describe his corporate web as a structure deliberately designed to conceal transactions and frustrate scrutiny. The island was not merely a destination. It was a financial instrument. Construction contracts, aviation fuel, maritime services, payrolls, security and logistics all flowed through the same tax-advantaged architecture. Visitors arrived by private plane into a jurisdiction engineered for reduced oversight. The physical environment itself became part of the tax shelter.

This was the service Epstein sold. By the late 1990s and early 2000s he had added billionaire Leon Black as a second core client. Between 1999 and 2018, Epstein collected roughly four hundred and ninety million dollars in fees, with approximately two hundred million tied to Wexner entities and about one hundred and seventy million to Black. For a supposed billionaire adviser, that was an extraordinarily narrow client base. Epstein did not compound his wealth through markets. He compounded it through concealment. He monetised invisibility. Each offshore structure he built for clients mirrored those he built for himself. His fiduciary role and personal enrichment became indistinguishable.

Epstein used to say he “invested in people.” Not companies, not public offerings, but flesh-and-blood access: billionaires, officials, scientists, heads of universities. Men who chaired boards. Men who drafted policy. Men who could change tax codes with a phone call. Men who had so much money that it came with incredibly high tax bills - bills they didn’t want to pay, at least not in full if they didn’t have to. That’s where Epstein came in.

To maximise his income and reduce his own tax outgoings, Epstein obtained generous tax concessions: his companies were approved for a program that cut corporate income tax by as much as ninety percent, reduced gross receipts and excise taxes, and gave him exemptions and credits that dramatically lowered his federal liability. The result was that fees paid to him by Wexner and Black could be booked through entities in St. Thomas and Little St. James, transforming tens of millions that would once have been taxed in the continental United States into lightly taxed Caribbean revenue. In other words, he could get richer and richer. And he did.

There is no public evidence that Epstein was some sort of trading genius delivering spectacular returns. What the record shows instead is that his value lay in discretion and structure: he built and tended opaque vehicles that let clients reduce their tax bills, move money offshore, and keep assets hard to trace.

Here and there, you see the same logic applied to his own wealth. Epstein’s private island in the Virgin Islands was held through a company apparently created for that single purpose. Aircraft were owned by entities with nondescript names. Philanthropic foundations in New York and New Mexico gave him a respectable public-facing profile while acting, conveniently, as yet more legal containers for money. In one complaint, Virgin Islands authorities describe his network of companies as a “web” designed to “conceal the true nature of transactions” and allow the movement of funds “with minimal scrutiny.”

That architecture would later become a central issue in lawsuits brought by the U.S. Virgin Islands government after Epstein’s death. Regulators alleged that Epstein’s entire territorial presence had been structured to exploit tax benefits while facilitating crimes that the territory had failed to stop. The Virgin Islands eventually reached a large settlement with his estate, reclaiming a portion of the tax benefits and levying penalties for years of regulatory failure.

It is the same mechanic over and over: build a structure that keeps the rich out of sight, then charge for the keys. Epstein did not manufacture a commodity or build a platform. His trade was plausible deniability.

You would think that a conviction for sex crimes involving a minor would burn that trade to the ground. In 2008, he pleaded guilty in Florida to soliciting prostitution from a minor, after a woman named Haley Robson (who was recruited by Virginia Giuffre) found the minor in her local area of West Palm Beach, took her to Epstein, and told her to lie that she was over 18 before encouraging her to engage in sexual activity. Epstein served a short sentence under a work-release scheme that let him leave the county jail for up to twelve hours a day, six days a week.

He registered as a sex offender. For most people, that would have meant permanent exile from polite society. For Epstein, it was merely a pause.

The calendar and email records that have emerged in recent years sketch what came next. Within a very short time after his release, Epstein was back hosting dinners at his Manhattan townhouse, flying to Europe on private jets, and sitting across from men whose names would later reappear in the so-called Epstein files. He continued to donate money to prestigious institutions. Harvard never returned millions he had already given; his name was removed from some spaces, but researchers still used funds that traced back to his accounts. At MIT’s Media Lab, administrators quietly courted his donations even after they were warned about his conviction, discussing internally how to list his contributions in a way that obscured his identity while keeping the cash.

Epstein kept his seat in the intellectual salons that mattered to him. Academics shuttled through his living room to talk about artificial intelligence, physics, cosmology, and the future of human cognition, sometimes leaving with cheques.

Politicians and policy figures kept their own kinds of appointments. Calendars unsealed through litigation show that William Burns, now director of the CIA but then a former ambassador and deputy secretary of state, met Epstein multiple times in Washington and New York during the years when Burns was between official posts. Email traffic and later investigations revealed that Epstein actively cultivated senior officials from central banks, finance ministries and international organisations, offering introductions, social access, and occasionally the use of his aircraft. Epstein also maintained close ties to figures in Israeli politics and defence technology. He partnered financially with a former Israeli prime minister in a cybersecurity firm that marketed surveillance tools to governments. He hosted delegations of foreign intelligence-linked entrepreneurs at his properties. This blending of finance, intelligence-adjacent technology, and elite social life was not an accident. It was his operating environment.

Noam Chomsky’s name appears in Epstein’s private scheduling records, attached to meetings in New York and invitations to dinner at the townhouse. Later, when congressional committees released a tranche of Epstein’s correspondence, the material included personal letters in which Epstein and Chomsky exchanged views on politics and philosophy, along with routine arrangements about travel and visits. Journalistic summaries of those emails note that Chomsky’s wife sent Epstein friendly messages and that at one point an Epstein-linked account wired around two hundred and seventy thousand dollars to assist Chomsky financially during his divorce. Chomsky has not denied the relationship. He has argued that it is his business whom he meets and that the money did not come from Epstein personally.

He was not alone. Many scientists rationalised their presence in Epstein’s orbit by telling themselves that he was a sinner who had paid his debt and that refusing his cheques would only harm their work. Others admitted privately that Epstein’s dinners were unrivalled opportunities for networking at the highest level. The gravitational pull of money and proximity to power proved stronger than reputational risk.

When you understand how resilient his standing remained in Western elite circles, and the famous and influential figures that surrounded him, you begin to see why someone in the murky depths of Moscow might decide that this disgraced American financier was still very much worth talking to.

Sergei Belyakov did not look like a spy. In official biographies, he was a soft-spoken economic official, a man of meetings and plenary sessions and investment forums. What those biographies did not advertise was his education at the FSB Academy, the training ground for Russia’s intelligence operatives and security bureaucrats. Investigators later reconstructed his path: study at the Academy in the 1990s, service in the border troops, then a steady rise through roles tied to economic policy and investor relations. By the early 2010s he had become Deputy Minister of Economic Development and an assistant to powerful figures such as Elvira Nabiullina, later the long-serving governor of Russia’s Central Bank, and First Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov. Then he moved into a role that brought him even closer to the Kremlin’s showcase: head of the foundation that organises the St Petersburg International Economic Forum, the annual gathering Russia uses to court global investors and project economic legitimacy under sanctions.

If SPIEF is Russia’s Davos, Belyakov was one of the men behind the guest list. And his FSB Academy background meant he was the kind of technocrat who understood that “investment climate” and “operational leverage” could mean more than just tax rates and infrastructure.

By 2014, Epstein and Belyakov were in contact.

They exchanged emails and gifts. After one of their meetings in the spring of that year, Belyakov wrote to Epstein that few people “can open new horizons and prospects” like him, and thanked him for a “nice gift.” What that gift was remains unspecified. During their exchanges, Epstein proposed recruiting high-profile Western guests for SPIEF and offered advice on how Russia might weather Western sanctions imposed after the illegal annexation of Crimea.

By 2015, the relationship had matured enough that Epstein felt comfortable writing to Belyakov as if he were a fixer. In a July email Epstein wrote that he needed a favour and identified “a Russian girl from Moscow,” Guzel Ganieva. He said she was attempting to blackmail a group of powerful businessmen in New York and described the situation as “bad for business.” He noted that she had just arrived in New York and was staying at the Four Seasons on 57th Street. He ended with one word: Suggestions. Belyakov replied with what read like an intelligence-style profile. He outlined her business patterns, reported that she had no powerful patron, noted that she had been involved in numerous “hard stories,” and concluded that denying her access to the United States would pose a great threat to her business. There is no public record that any immigration or visa action followed. But the message is unambiguous: a convicted American sex offender was seeking help from a Russian security-trained official to manage a reputational and sexual-finance crisis using geopolitical leverage rather than courts.

The documents show Epstein advising Belyakov on broader economic strategy as well. He proposed financial instruments, credit mechanisms, and even a new multinational currency model as ways for Russia and allied economies to circumvent Western financial pressure. He offered to use his personal network to bring Western elites, investors, and technologists into sanctioned Russian forums, packaging attendance itself as a form of legitimacy. This was not ideological alignment. It was transactional utility.

Years later, in 2021, Guzel Ganieva publicly accused Leon Black of years of sexual coercion and abuse. She described Epstein as Black’s closest confidant and alleged that she had been taken to Epstein’s Palm Beach home while Epstein was technically incarcerated, where his assistant attempted to pressure her into sex with him. She refused. Her allegations described a pattern of contact, pressure and money that stretched back across multiple years. She alleged that Black paid her for sex and companionship while attempting to control her movements and silence her through payments. She alleged sadistic conduct, psychological coercion, and the constant presence of Epstein in Black’s world as both confidant and facilitator.

She sued Black for sexual assault and human trafficking. Black countersued. A campaign emerged portraying her as a Russian intelligence officer based on a misidentified name from a foreign intelligence leak. Investigators later established conclusively that the alleged officer and Ganieva were not the same person. No intelligence agency has ever substantiated any claim that Ganieva worked for Russian security services. Her lawsuit was dismissed in 2023 not because a court ruled her abuse claims false, but because she had previously signed a non-disclosure agreement with Black accompanied by a payment of about nine and a half million dollars and had not returned the money. On strict contract grounds alone, the lawsuit was barred. The underlying allegations were never tested before a jury.

Another Russian vector surfaced in 2018 as Donald Trump prepared for his summit with Vladimir Putin. Epstein wrote to a European intermediary claiming that Russia’s late UN ambassador Vitaly Churkin had “understood Trump” after conversations with him and that Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov could gain insight into Trump by speaking with Epstein directly. The message positioned Epstein as a private interpreter of American presidential behavior at a moment when intelligence agencies and foreign ministries worldwide were still struggling to read Trump’s intentions. There is no evidence Lavrov responded. Churkin was already dead. But the email again shows Epstein attempting to sell himself as a back-channel between global power centers.

Around the same period, Epstein privately claimed that he had flown to Moscow to meet Vladimir Putin and had been providing services over the final decade of his life. No independent corroboration of such a meeting exists. Placed beside the documented correspondence with Belyakov and the overture to Lavrov, however, the claim fits a consistent pattern of self-presentation as a geopolitical intermediary operating in the shadow spaces between finance, intelligence, and diplomacy.

Investigators later concluded that Epstein’s assistance to Belyakov and his circle extended into advising Russian economic officials on navigating sanctions and continuing to recruit elite Western participation for Russian investment forums during periods of diplomatic isolation. SPIEF is not merely an economic conference. It is a stage on which Russia performs normality for domestic and foreign audiences. Escort agencies openly recruit for the event. Western executives drink champagne with sanctioned oligarchs within sight of security officers trained in surveillance and counterintelligence. Hotel corridors fill with translators, lobbyists, fixers and itinerant models. It is an environment where kompromat does not need to be manufactured. It only needs to be collected.

In such a world, Epstein’s core talents were unusually valuable: discreet money movement, reputation-laundering, and controlled social access. He had supplied those exact services to American billionaires for decades. Now the same skills were being quietly repurposed at the intersection of sanctions, propaganda and geopolitical influence. No court has formally declared that Epstein worked as a Russian intelligence asset. But the documentary record now shows that he cultivated, advised and sought assistance from figures at the heart of Russia’s post-sanctions economic outreach.

His fortune grew out of helping a tiny class of ultra-rich clients hide and move their wealth. His social power survived a criminal conviction because the institutions that benefited from his money chose not to exile him. His Russian contacts emerged precisely when Russia needed bridges to Western capital and legitimacy most strongly. Seen together, they form a single continuous strategy: access in exchange for invisibility.

The black door on East 71st Street has been repainted now. When I visited it last year, its new owners were renovating it throughout. The island in the Caribbean has been sold. The planes have new registrations. But the offshore system that produced Jeffrey Epstein remains intact. Trusts still hum beneath the global economy. Conferences still pair oligarchs with intellectuals beneath chandeliers. Men trained in security services still move quietly between state power and private capital, always looking for the next intermediary. What the documents now show is not that Epstein was an anomaly. They show that he was a mechanism.

I have a hard time with the Ganieva and Pierson allegations. It's easy to pull the "Epstein card" so to speak, especially after the example set by big law firms for years.

On the question of Jeffrey Epstein's money, I found it amusing that Senator Ron Wyden thought Leon Black giving Epstein a couple million he had initially held back was suspicious, based on the investigation by his old management firm. When the real question is if Epstein had salacious "dirt" on Black why didn't he just expose it instead of whining about consultation fees for two whole years?? 😂