COLD CASE: Life, Death, and the Steps Between - The Staircase 'Murder'

A famous writer was imprisoned, then released, over the death of his wife, whose blood-drenched body was found at the bottom of a staircase. But was it an accident as he contends... or was it murder?

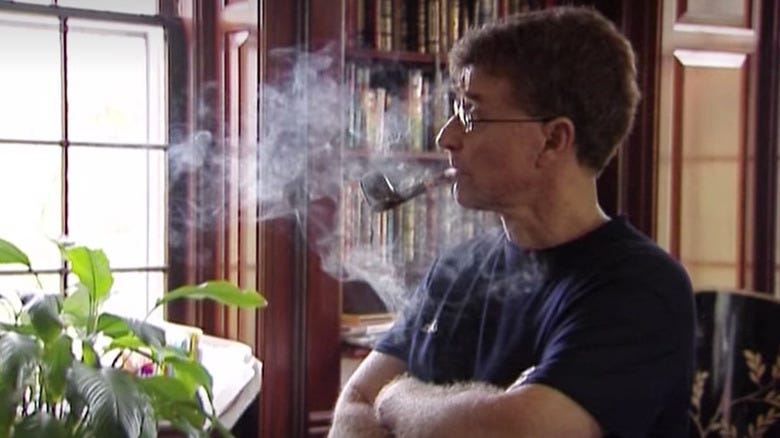

The house on Cedar Street lies low and quiet beneath the Durham night, its pale columns holding the last of the streetlamp’s fading amber. The neighbourhood has folded into itself. No traffic. No voices. Only the steady work of insects in the trees and the soft electrical hum from windows left awake for late television. Inside the Peterson home, the rooms open wide and deliberate, designed for permanence. Polished hardwood floors. Books pressed shoulder to shoulder in tall shelves. Framed photographs spaced to suggest continuity and order. In the study, the faint, aged sweetness of pipe tobacco still hangs in the drapes, a ghost of routine that has seeped into fabric over years. This is the private architecture of success. The kind that assumes tomorrow will resemble yesterday.

It is shortly after midnight on December 9, 2001.

Michael and Kathleen Peterson have been sitting by the backyard pool, drinking wine, talking. The air is warm for winter. At some point Kathleen goes inside first, moving through the rear door toward the narrow staircase that climbs to the bedrooms. Michael remains outside for a time longer. What happens next is fixed only in blood and testimony.

At 2:40 a.m., Michael Peterson calls 911.

“My wife had an accident,” he says. His voice breaks as he speaks. “She fell down the stairs.” He tells the dispatcher she is still breathing. “There’s blood everywhere.” He sounds confused, frightened, insistent that help come immediately. He cries. He repeats himself. He does not hang up.

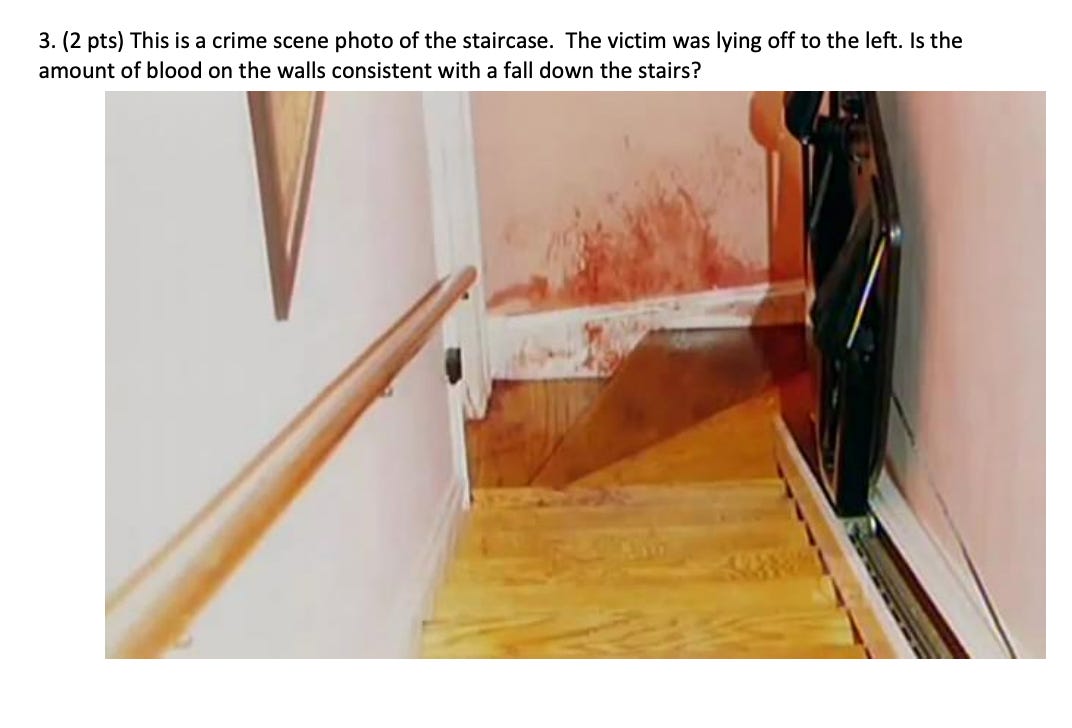

When paramedics arrive, Kathleen Peterson is lying at the bottom of the rear staircase in a spreading pool of blood. Blood streaks rise up the walls beside her in long vertical lines. Fine mist dots the edges of the stairwell. Her breathing is shallow. She is transported to Duke University Medical Centre. She is declared dead shortly after arrival.

At first, the death is treated as a possible accident. Alcohol is present in her system. There are stairs. The two facts can be shaped into a narrative that requires no malice. That version will not survive daylight.

Detectives return to the house. They photograph the walls. They measure the distance between steps. They examine the blood patterns again and again. The volume seems excessive for a single fall. The vertical streaking does not align with gravity alone. The fine mist suggests motion through air, not simple collapse. They observe that the metal fireplace blow poke normally kept beside the hearth is missing. The scene no longer behaves like tragedy. It begins to behave like intent.

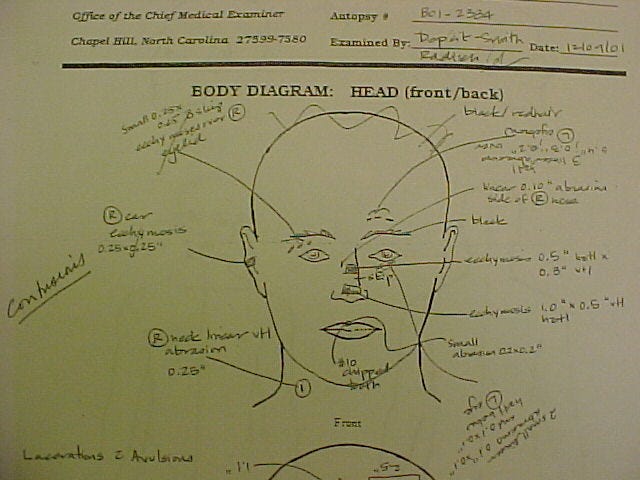

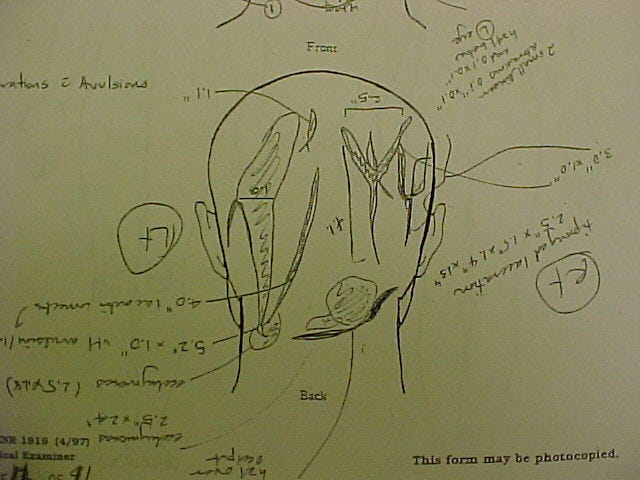

The autopsy confirms the problem.

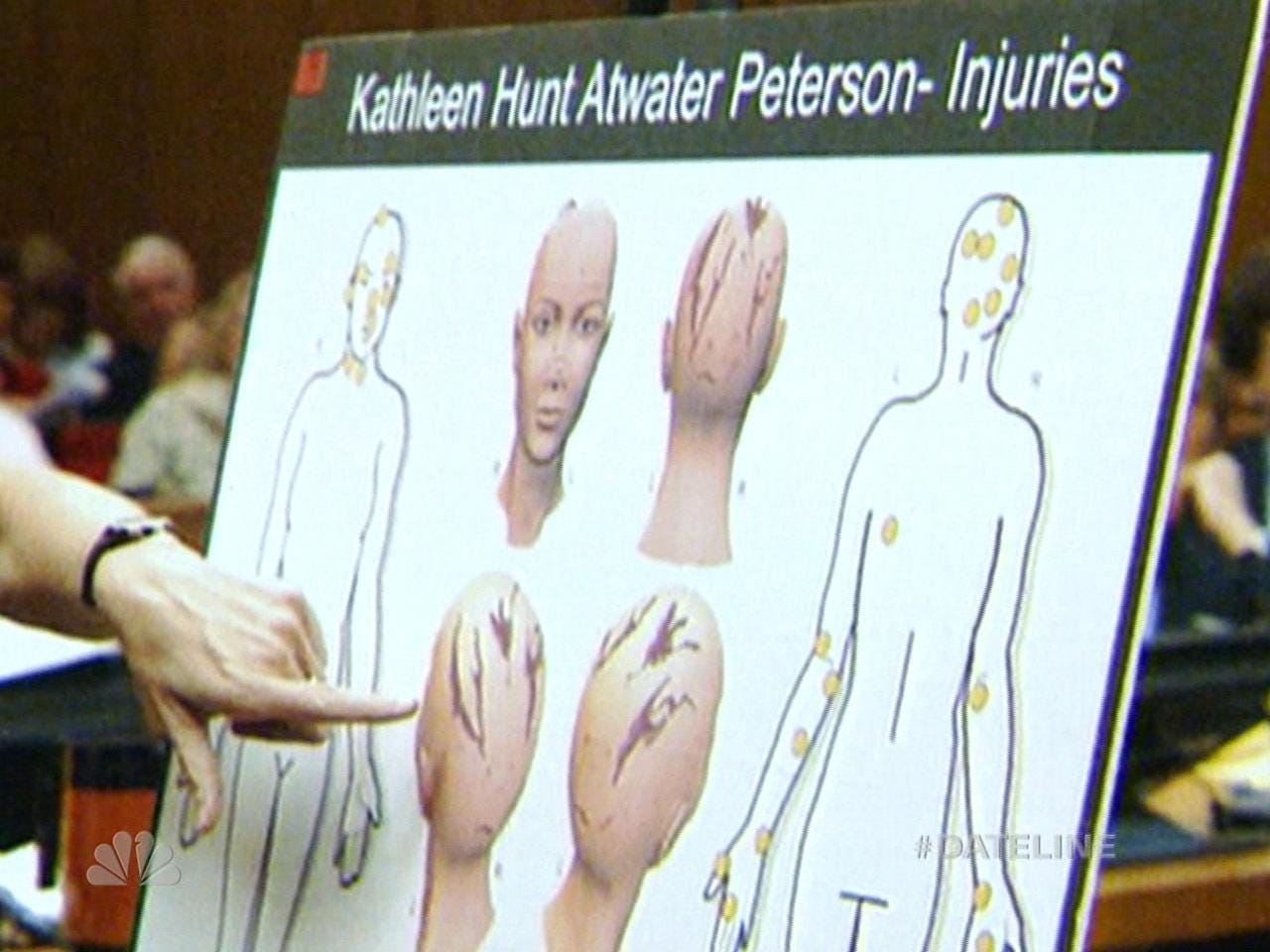

Kathleen Peterson has sustained at least seven deep lacerations to the scalp. Some of the wounds are several inches long. The edges are jagged. There is haemorrhaging in the soft tissue of her neck and surrounding areas. There are no skull fractures. The medical examiner rules the manner of death a homicide caused by blunt-force trauma and estimates that Kathleen lived for over an hour after the initial injuries, bleeding slowly over time.

Michael Peterson tells police that Kathleen slipped. He says she had been drinking. He says she must have lost her footing on the stairs. He says the blood patterns were created when he tried to lift her, when he cradled her head, when he moved around her in panic. He denies any violent altercation. He repeats that he did not strike his wife.

In 2002, he is indicted for first-degree murder.

Michael Peterson is not an anonymous defendant. He is well known locally. A former Marine officer and Vietnam veteran, he later worked as a journalist and novelist, publishing political thrillers and war-inspired fiction. He also wrote a newspaper column critical of local police and prosecutors and ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Durham in 1999. By the time of Kathleen’s death, he is a recognizable figure in civic life. At home, however, it is Kathleen who is the economic centre of gravity. A high-ranking executive at Nortel Networks, she earns the majority of the family’s income. By late 2001, Nortel is entering steep financial decline, and the prosecution will later argue that the household is increasingly dependent on her salary and that Kathleen is under mounting professional stress. She also holds a substantial life-insurance policy.

As detectives look deeper into the marriage, they uncover a second life.

Michael Peterson has been secretly seeking sexual encounters with men. Email correspondence is introduced showing explicit exchanges and arranged meetings. One man testifies that Peterson had scheduled a sexual encounter with him just days before Kathleen’s death. The prosecution does not frame homosexuality itself as evidence of guilt, but rather secrecy. They argue that Kathleen either discovered or was on the verge of discovering this hidden life and that the confrontation that followed was physical and fatal. The defence responds that Kathleen knew of Peterson’s bisexual history, that she was not intolerant, and that no evidence places any argument in the house that night.

The case against Peterson is built primarily on blood.

The prosecution’s central expert is a State Bureau of Investigation bloodstain analyst. He testifies that the patterns in the stairwell show repeated impact. He explains fine misting as cast-off created when a bloodied object is swung through the air. He tells jurors that Kathleen was struck multiple times at the base of the staircase and that the distribution of blood proves motion and force incompatible with an accidental fall. He testifies with scientific certainty.

The defence dismantles that certainty piece by piece.

A renowned forensic pathologist testifies that blunt-force trauma from a metal weapon should have fractured the skull. The absence of fractures, he argues, is inconsistent with a beating. A bloodstain interpretation expert demonstrates that fine mist can also be produced by coughing blood from the mouth. In a moment that becomes symbolic of the trial’s forensic warfare, he demonstrates this to jurors with ketchup sprayed from his mouth across a surface. He testifies that gravity, movement, prolonged bleeding and attempts to render aid can create complex patterns that mimic cast-off. The jury is left to choose between competing sciences.

The alleged weapon becomes the metal at the centre of speculation.

The fireplace blow poke is missing in early photographs. The prosecution suggests it as the murder weapon: hollow, metal, light enough to split scalp without fracturing bone. For months it cannot be located. Then, during the trial, one of Peterson’s sons discovers it in the garage. It is dusty, undisturbed, bearing no visible blood. Tests reveal no tissue or DNA. The prosecution argues it may have been cleaned. The defense argues that a murder weapon cannot simply sit unnoticed in a garage after multiple searches. Even some jurors later admit they doubted the blow poke was used. They convict Peterson anyway.

Then the case fractures backward in time.

In 1985, while living in Germany, Michael Peterson was close friends with a neighbor named Elizabeth Ratliff. After Ratliff’s husband died, the families remained deeply connected. One evening, the Petersons dined at her home. Michael stayed behind to help put her two daughters to bed. The next morning, the nanny arrived and found Ratliff dead at the bottom of her staircase. Authorities at the time ruled that she suffered a spontaneous brain haemorrhage linked to a blood clotting disorder and then fell. No homicide was suspected.

Years later, those two daughters would be adopted by Michael Peterson and raised in his home.

Before Kathleen’s murder trial, prosecutors reopened the German investigation. Ratliff’s body was exhumed nearly eighteen years after burial. A second autopsy was performed by the same medical examiner who handled Kathleen’s case. This time she ruled Ratliff’s death a homicide by blunt-force trauma. The state did not charge Peterson for that death, but presented the jury with the image of two women dead at the base of staircases, with the same man the last known adult present. The defense argued that the original ruling was accidental, that reclassification decades later is unreliable, and that memory-based testimony about blood after nearly twenty years is inherently flawed. The pattern nevertheless embedded itself in the case.

Inside the courtroom, the family collapses along opposing lines.

Kathleen’s sister Candace and her daughter Caitlin initially supported Peterson after the death. After learning of his secret infidelities and reviewing the autopsy, both changed allegiance. They testify for the prosecution that they believe he killed her. They speak of betrayal and deception. Peterson’s sons and adopted daughters testify for the defence, describing a calm father and a peaceful home. The jury observes a single family fractured into incompatible certainties.

The trial stretches for months. It becomes one of the longest and most heavily covered in North Carolina history. Jurors listen to experts debate blood for days at a time. They hear about bank accounts, insurance policies, marital tension, sexual secrecy. They see graphic autopsy photographs. They hear about a second staircase in another country. They are asked to hold science and coincidence inside the same verdict.

On October 10, 2003, after more than eight days of deliberation, the jury finds Michael Peterson guilty of first-degree murder. He is sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

From that point, the law seems finished with him.

Appeals are filed and denied. Higher courts uphold the conviction. A civil wrongful-death suit brought on behalf of Kathleen’s estate results in a judgment against him. He files for bankruptcy. The public absorbs the verdict as final.

Then the forensic science that built the conviction begins to disintegrate.

A state-wide audit of the State Bureau of Investigation’s forensic unit reveals widespread problems in bloodstain testimony. The analyst who testified in the Peterson trial is found to have exaggerated his experience and overstated the certainty of his findings in multiple cases. He is dismissed from the SBI. At a post-conviction hearing, the judge rules that his testimony was materially false and misleading and that the prosecution relied on it. In December 2011, the court orders a new trial.

After eight years in prison, Michael Peterson is released on bond under house arrest. He wears an electronic ankle monitor. He is now visibly aged. His hair is fully white. His posture is slower. The man who returns to the Cedar Street house is not the man who left it.

As legal certainty unravels, the public narrative expands again.

The case is documented across years, following the original prosecution, the family rupture, the appeals and the scandal that overturned the conviction. Viewers watch lawyers argue in real time. They watch family members age. The case transforms from a murder trial into a study in how truth fractures under inspection.

As science and law unravel, a stranger explanation enters the record.

A Durham attorney studying the autopsy photographs notices that several of Kathleen’s scalp wounds are narrow, curved and triangular. He later discovers that microscopic feathers were catalogued in hair Kathleen had pulled from her head and was clutching in her hand. A small wooden sliver resembling a tree fragment was logged with the same evidence. He proposes that a barred owl attacked Kathleen outside the house, striking her head with talons, causing immediate scalp lacerations and disorientation. Bleeding heavily, she ran inside and collapsed at the staircase where she continued to bleed.

The original medical examiner rejects the theory. Prosecutors dismiss it as implausible. Other forensic experts later submit that it cannot be completely ruled out. The owl becomes part of the case’s strange second life, an explanation so unlikely it becomes unforgettable.

By 2016, the state prepares for a full retrial. Peterson is now in his seventies. The risk of another life sentence looms. In February 2017, he enters an Alford plea to voluntary manslaughter. Under the plea, he maintains his innocence while acknowledging that the prosecution has sufficient evidence to secure a conviction. He is sentenced to time already served and walks free the same day.

Legally, the first-degree murder conviction dissolves without a new jury verdict replacing it. The case ends without certainty, without exoneration, without reaffirmed guilt.

Kathleen Peterson remains dead at the base of the staircase. Michael Peterson remains a man once convicted of her murder and later freed. Elizabeth Ratliff remains a woman whose death was reclassified as homicide decades later without a charged suspect. A blow poke vanished and reappeared without explanation. A forensic expert lost his career. Microscopic feathers remain catalogued in evidence.

Years later, after prison, after appeal, after compromise in place of verdict, Peterson tried to sum it all up with a borrowed line. It was not a legal statement. It was a literary one. A sentence lifted in spirit from Crime and Punishment, the novel he had long admired, the book that insists guilt does not end with the act itself but spreads outward into every life it touches. Dostoevsky’s line is colder and more exact: “We are all responsible for all.” It is a theory of shared consequence, of crime as a contaminant that moves through families, through witnesses, through time itself. Peterson used it to suggest that no one emerged untouched from the staircase. Kathleen was dead. He had lost years of his life. Children had taken sides and lost one another. Truth itself had fractured.

“All are punished,” he quietly said.

But were they?